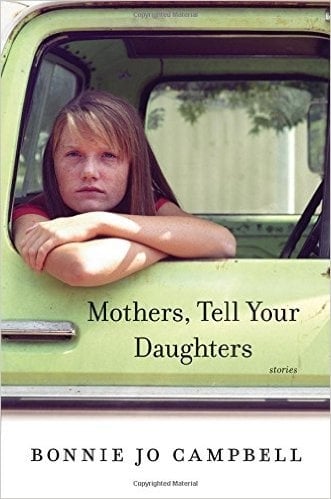

Rural noir seems to be one of literature’s most popular genres at the moment. 2015 gave us Tom Cooper’s The Marauders, Brian Panowich’s Bull Mountain, and David Joy’s Where All Light Tends to Go. These novels, with their tough, violent, and gritty characters, were recommended in bookstores across the country. Now, just in time for all of the annual “best of” lists, enters the critically beloved, rural noir goddess herself, Bonnie Jo Campbell.

Campbell’s last short story collection, American Salvage, appeared in 2009. It was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award and the National Book Award. Her latest offering, Mothers, Tell Your Daughters, is sure to build a similarly impressive awards tally. It’s certainly worthy of such accolades.

Mothers, Tell Your Daughters finds Campbell in usual form, digging into rural America, and specifically the women who inhabit this world. Campbell isn’t preferential in the types of women she writes about. Some are smart; others are ignorant to life in general. Some of these women are funny, while others are cruel. Flaws are bared in many of Campbell’s characters, and motherhood is only a thought away.

In one of the lighter, but more enjoyable, stories in the collection, “My Dog Roscoe,” Campbell presents a woman named Sarah, who can’t discern between actuality and the supernatural. Sarah introduces herself by establishing her oddness: “As my big sister predicted from her cell in the county jail, I became pregnant early into my marriage to Pete the electrician. The tarot reading Lydia did for me was the last before one of her cellmates reported her so-called satanic activities to the authorities and got her cards taken away.” Yes, Sarah is totally weird, but she’s also likeable.

A dog-named Roscoe visits Sarah. Roscoe, Sarah believes, is her dead (but definitely reincarnated) ex-boyfriend, Oscar. Being reunited with the past love of her life might be okay, but Oscar wasn’t a winner. Sarah says, “If Oscar had lived, he probably would have turned his life around and behaved better eventually.” And Sarah’s hopefulness that she can change her dead boyfriend is where “My Dog Roscoe” gains most of its traction.

She struggles with what she should do with the dog. Should she love him? Is it her duty to care for Roscoe? She tells him, “It’s always just been me and you. Nobody else can see what keeps us coming back to each other. Nobody else understands our animal magnetism.”

Much of “My Dog Roscoe” revolves around unspecified guilt and unresolved feelings. And this is supposed to be one of the “lighter” stories.

Campbell’s title story is the toughest of the bunch, and it’s also the best one. “Mothers, Tell Your Daughters” is told from the mind of a dying woman who cannot find the strength that she so loves to say what she wants to say to her daughter.

The mother here is strong. She “inhaled gunpowder, spray paint, aerosol wasp killer, smoke from everything that burned.” She cares so much about being strong that her loss of strength seems to be the one thing that hurts her the most. She reflects on how much she’s lost as she lays, dying in her hospital bed: “You remember the good old days, when I could drink and smoke all night, when I could feed more kids than any woman alive and love a man better. Now I’m dying in this house I was born in, dying with no wine, no cigarettes, no laughing or singing.”

The mother doesn’t just admire her own strength, but it seems to be the trait she most wanted to instill in her daughter. She says, “After your daddy left, I tried to raise you to know men and to not fear them, so you wouldn’t be taken by surprise. I figured that if any of them bothered you, you would make a fuss, the way you made a fuss when I wanted you to get out of bed early and haul buckets of water.” It’s a harsh approach to motherhood, but it’s the mother’s truth in “Mothers, Tell Your Daughters.”

The story is one of the most beautiful internalized pieces of fiction that I can recall reading. It has a quietness about it that creates an almost surreal reading experience. The ending is brutal. The mother might be old; she might even be dying, but she’s not weak minded. She’s a fierce woman who doesn’t seem to regret the difficult life she’s lived.

“Home to Die” is another standout that tells about a wife taking care of her cruel husband, who is dying. “The Greatest Show on Earth, 1982: What There Was” and “Daughters of the Animal Kingdom” tackle women handling pregnancy.

There is a lot to savor in Campbell’s writing. The prose simmers on the pages, and the dialogue pops as each new story begins. Sure, there’s devastation, hardships, and damage all around the women in each of Campbell’s stories, but there’s also redemption and grace.

Mothers, Tell Your Daughters shows rural America as it truly is: often messy, sometimes scary, but always tough.