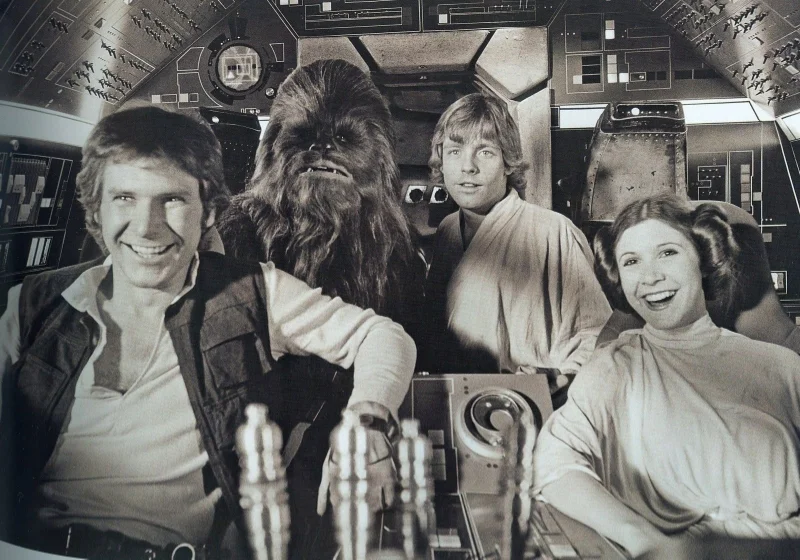

Mark Hamill, Carrie Fisher, and Harrison Ford in the original Star Wars (Image © Lucasfilm).

Star Wars. Few film series have had the power to sustain our collective imagination as George Lucas’s unique hybrid of science fiction and fantasy has. Filled with wookies, droids, Hutts, Jedi, Sith, and yes, midi-chlorians, all six films in the Star Wars saga, even the oft-maligned prequels, have been cultural events upon their release.

Now, with Disney and J.J. Abrams ready to once again make the jump to hyperspace, The Drunk Monkeys Film Department begins a year-long discussion series featuring each installment of the series, starting with the 1977 classic, and culminating this December with The Force Awakens.

Donald McCarthy, Lawrence Von Haelstrom, and Matthew Guerruckey will discuss each film, along with a guest writer from the Film Department (and you, of course, in the comments below). First up is Scott Waldyn, who joins us for a discussion of Star Wars: A New Hope, the film that started it all.

Matthew Guerruckey, Editor-in-Chief: I was born in 1979, two years after the original Star Wars was released, so it’s always existed for me. I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t a fan. These days there are so many different things that vie for a kid’s attention, at all times, so fandom can get fractured. But in that era, nothing could compete with Star Wars.

Certain things or people appear at exactly the moment that the culture at large needs them. The Beatles came along fifteen years after the atomic bomb dropped, and the world had tried, for the second time in a generation, to completely undo civilization. People needed release, and that release had to come in positive wrapping. If the Beatles had sneered at the world, or carried the same dangerous swagger as The Rolling Stones, they wouldn’t have become the phenomenon they did.

It’s the same with Star Wars. The cultural landscape it grew out of should have strangled anything so deliriously optimistic. George Lucas ran with a serious group of filmmakers--the leader of this crew, Francis Ford Coppola, had built his reputation on a film, The Godfather, which ends with the lead character selling, or at least nullifying, his soul. In the Godfather series, Michael Corleone is what would have happened to Luke Skywalker if he had accepted Vader’s offer in Cloud City.

But that was America. America was Watergate. America was Vietnam. America was gas rations and malaise and grittiness. Cities were cauldrons of distrust and fury, and small towns were going broke and shutting down. The cinema of the 70’s reflected that harsh reality, with a standard of realism that had never been seen before. These films were tough and kinetic, and challenged viewers.

And while the optimism of Star Wars bucked that trend, it’s still very much a product of the 70’s (and I’m not even talking about Luke’s shaggy hairdo). The galaxy far, far away is grimy and weird. There’s distrust, intolerance, and oppression. There are dirty robots, dirty people, and even our heroes are murderers (yes, I’m talking about Han Solo, and yes, we will explore that much more later). But at the center of this story is an innocent, a 19-year-old dipshit who believes with all of his naive heart that he can change the world. And then he does it.

It’s important to have a character that pure at the core of the movie. We get so involved in the story because it’s Luke that we’re following. If this were Han Solo’s story, his air of cynical distance would make us question what sort of investment we should have in these characters and their world. Luke gives the audience the freedom to be in awe of everything on-screen, because no matter how dorky we may be, we’ll never be as dorky as Luke is.

Familiarity has stolen the novelty from moments like the opening shot of the Star Destroyer, or Vader’s first appearance on the Tantive IV. But at the time, audiences hadn’t seen--or felt--anything like this in years. Lucas is inviting the audience to feel a sense of awe and grandeur again. That emotional component is what gives the series its iconography, and, for people of my own generation, there’s a powerful nostalgia that goes along with it. People who complain that the changes that Lucas has made to the saga have ruined their childhoods need some perspective, but I do understand where that emotion comes from.

But I wonder what Star Wars means to people of a different generation. Donald, you came up in the prequel era. I wonder, what did the original Star Wars, which by the time you saw it had been given the fairly clunky subtitle A New Hope, mean to you as a kid?

Donald McCarthy, Features Editor: I saw Star Wars for the first time in either late 1996 or early 1997, when I was seven. I was at my aunt’s and we were playing a card game. She wanted me to watch Star Wars, but I was resistant and wanted to keep playing cards. I wasn’t interested in some weirdo sci-fi film. She said, “Okay, but I’m going to put it on so I can watch it while we play cards.” My seven-year-old brain did not pick up on her motives.

So the film began and I kept glancing over. About ten minutes in and the card game is forgotten and I’m watching this film, this film that’s like nothing I’d ever seen or even thought of. I simply couldn’t believe this existed. I wanted to train under Obi-Wan! I wanted to fly an X-Wing!

But then came the trench run. I was sweating, at the edge of my seat, gasping, shouting, and convinced that there was a real possibility that Luke might not be able to destroy the Death Star. And then, Oh My God, it’s Han Solo! “Yeehaa! Now let’s blow this thing and go home!” Just unbelievable. I could hardly handle it. I was almost ready to cry, but not from fear or sadness- from exhilaration.

And it jump-started my creative mind. I’ve been writing since I was young. After watching Star Wars, I suddenly became a writer- or as much as a seven-year-old can be one. I loved the film so much that I needed to create more of it and I needed to create more of it now. I remember my first written story was when I was seven and it was about a knight lost in the woods. I enjoyed writing it and thought maybe I’d do it again in the future. I wasn’t old enough yet to read the spin-off books so I had to create my own extension of the Star Wars film series. I credit my introduction to Star Wars as one of the main reasons that I’m here writing this. Otherwise, who knows what would’ve started me down this path?

Shortly after watching the initial trilogy, my aunt told me there were more Star Wars films coming and that the Special Editions would also be coming out (I ended up seeing the Special Edition of A New Hope in theaters with my dad who was thoroughly confused by the whole thing, but he was happy I was having a good time; I’m not so sure I understood that there were changes or what they meant). So my first viewing was of the original, but at no point was Star Wars, or even the original trilogy, somehow a stand alone event in my mind. I always knew there’d be more. And, dear God, I was hungry for it.

One aspect of my viewing that seems to put me at odds with most youngsters who watch it is the fact that Han Solo wasn’t my favorite character. Or even close. I thought Obi-Wan Kenobi was awesome and even though he was older I wanted to be just like him, knowledgeable, charismatic, compassionate, and powerful in a subtle way. To me, Han Solo was a bit of a jerk, not unlike some cocky kids I knew.

I also latched onto the setting. I wanted to know more about this universe. I wanted to see the other planets that would be mentioned. Where did all these weird aliens come from? What was all that stuff going on in the background? What was this weird war Obi-Wan mentioned? This place was a world, a real world with mysteries and beautiful sights. I think this is one reason why I enjoyed the prequels; I loved the universe Star Wars built and I wanted to dive deeper into its visuals.

I’m curious what characters others were drawn to. Was anyone a hardcore Grand Moff Tarkin fan?

Lawrence Von Haelstrom, Contributing Editor: I think my first favorite character was C-3PO. I was born in 1974. While I don’t think I actually saw it in the summer of 1977, I certainly saw it during the re-releases in 1978 and 1979. Halloween 1979 I was really excited about my store-bought C-3PO costume--one of those vinyl costumes with the plastic mask. However, when I got it home and opened it, I was disappointed and embarrassed to find that the costume had a picture of C-3PO on it. C-3PO didn’t have a picture of himself on him! Thankfully, it was a cold Halloween night and I was able to hide the failure in realism by keeping myself zipped up. I was C-3PO in a puffy coat.

A gold-plated lie.

It’s funny you mention Grand Moff Tarkin. He’s become one of my favorite characters. I see him as a bureaucratic stuffed shirt. He’s worked his way up the ranks into power not through actual competence but through adroit political ass-kissing. We’ve all worked for or with a Tarkin and seeing him get disintegrated on board the Death Star while refusing to evacuate in his moment of triumph is just delicious.

My appreciation of Star Wars--and A New Hope in particular--has grown with me. As a kid, it was all about the lasers and light sabres and space ships. As a pretentious teenager who read a synopsis of Joseph Campbell’s PBS series, it was an ur-text of the hero’s journey. Every viewing I come away with a new appreciation. My current favorite reading of it is as a post-modern film about film. (And this reading helps to appreciate the prequels.) It’s a pastiche of tired archetypes and cliched sequences reassembled in a new setting. As Donald mentioned, the casual references to other places and things--the Spice Mines of Kessel, a death sentence on twelve systems, the new VT-16--spark your imagination and make the events on film feel so much bigger and exciting. The jumble of familiar notions can sometimes feel like a child trying to make up a story. (My four year old daughter has created a rogues gallery of imaginary bad guys. There’s the Dronatic Robot who shoots knives and will kick you, and Blood Man who makes other Blood Mans by touching people. This is the sort of imagination that’s at work in Star Wars.) It doesn’t quite make sense, but it sure is fun. Ultimately, Star Wars is a smart movie about the fun of dumb movies.

Sometimes I wish there was just this one movie. No sequels, no prequels, just this one odd adventure that pretends it’s part of this larger saga. This one Star Wars film does such a great job of igniting your imagination, no other follow-up is needed.

What do you think about the notion of Star Wars as a stand-alone movie? Does Star Wars need sequels to make it what it is?

Scott Waldyn, Contributing Writer: I don’t know when I first saw Star Wars. I was born in 1987, just four years after Return of the Jedi concluded the original trilogy and right on time for said trilogy to make its rounds on premium cable channels, and as far as I could tell, Star Wars had always been there. It was an old tale adults told their children. It was a fable, a relic, an ancient legend — passed down from generation to generation, sliding into a hopeful youth’s hands at just the perfect moment.

My first copy was recorded on to a VHS tape from HBO. The tape sat on the bottom shelf in our movie cabinet, in a plain black box with the tiniest of handwriting having scribbled “Star Wars” in between two other movies. A blanket of dust coated the box, with the imprint of small fingers as the only indication it had ever been disturbed. The bottom shelf was reserved for recorded movies only. It was cinematic purgatory — a Memorex limbo. But it was in that dank, dark part of the library that lost treasures felt the most secretive, fruitful, and cathartic. No one ventured there, save for the adventurous and the brave, and I so desperately wanted to be brave, to be a hero.

When I was eight years old, this archaeological find became everything. It was a portal away from home, an open gateway to greater imaginations that existed beyond the repetition of school and an uneven home life. It was a starting line, one that begged you to conjure up your own mythos. You could be the hero. With a pen and paper or some action figures, you could guide the course of events, like The Force, building and co-creating in this universe.

The fact that sequels exist is, in most cases, a bonus expanded mythos, but they aren’t necessary. This one dream, this one flight of fantasy, was the first step beyond the veil of limitation. It was a dream where anything was possible, where good and evil culminated in iconic battles in an ever-expanding galaxy. It was a way of tapping into something limitless and making sense of the world around us, of pulling us up when we’re sad, alone, or feeling powerless.

One film or many, Star Wars’ mere existence is magical. Judging by the large amount of novelizations, spin-offs, video games, toys, fan fiction, fan films, and so on, it’s sparked that lightning bolt of imagination in countless people worldwide, too. Simply put, this one film managed to do something very few works of art accomplish — it created a zeitgeist. And that doesn’t matter if there’s only one film or seven.

I mentioned licensing and a variety of Star Wars-related material that has been birthed since 1977. Is there any particular medium Star Wars has crossed into that solidified what the franchise means to you?

Matthew Guerruckey: Well, as I say, when I was a kid, Star Wars, and Star Wars-related merchandise, was inescapable (not that I had any particular desire to escape them). So I had the action figures, I had the books, I had the sheets. When I was five-years-old, I got one of those plastic green lightsabers that hummed when you swooshed it around. It was incredible. Then my mom threw it out during the next year’s spring cleaning, and two days later this squirrelly neighbor kid was playing with it. He’d dug it out of the trash. That’s how cool this thing was--he dug it out of the trash, and he was right to do so!

But Star Wars fandom leveled out after Return of the Jedi. There were the Marvel comics, but nobody took those seriously, and there were books here and there, but until Heir to the Empire, none felt like the real deal. But even the Zahn series is pretty silly, when it comes right down to it (a clone of Luke Skywalker named Luuke? Get the fuck out of here). In time the Expanded Universe got so large that it began to dilute the movies themselves. The attack on the Death Star began to feel less important than it had been, and as characters were added to the universe, Luke, Han, and Leia began to feel more like small, if critical, cogs in a larger world instead of the hub around which the Star Wars Universe revolved.

But the real problem with this additional Star Wars material was that much of it didn’t feel like Star Wars at all. That’s because what really defines the original trilogy, and especially A New Hope, is a straight-forward approach to storytelling that jumps from adventure to adventure without adding superfluous elements. The economy of story in A New Hope is remarkable: the droids lead to Luke, Luke leads to Obi-Wan, Obi-Wan leads to Han, Han leads to Leia, Leia leads to the Rebels, the Rebels blow up the Death Star. Done, go home. Everybody gets medals. Except, you, Chewie.

What he's shouting translates, roughly, to "Ingrates." (Image © Lucasfilm)

Along the way, we meet these really bad guys, who are really just a bunch of soulless bureaucrats. How bad are they? They burn people alive. That’s pretty bad, all right. But even worse then those guys is this cat named Darth Vader. How do you know he’s bad? Take one damn look at him and you know. But along the way, Lucas does not stop the story for any extraneous nonsense. Every piece of information that we’re given adds character motivation or advances the plot.

There’s really only one scene in all of A New Hope that could be cut out without affecting the narrative flow, and that’s the trash compactor scene. But you wouldn’t cut that, because it’s too damn fun, and really adds to the “1940’s serial” feel of the movie. Star Wars is a series of cliffhangers that get immediately resolved, and in that way, feels like twenty movies in one (which, as any fan of Flash Gordon or Kurosawa will tell you, it is).

So a novelistic approach to the Star Wars Universe has always felt like a mistake to me, on some level. That’s not to discount some really fun stories and characters that have come along in the past few decades of Expanded Universe material, but this story belongs to the medium of film. For better or worse, the prequels feel like Star Wars because they’re films. Because they follow, for the most part, that self-contained serial structure. And because of the music.

Guys. The music.

If there’s one thing that makes Star Wars what it is, it’s the John Williams score. The music is the way in which Star Wars announces its intentions--the 20th Century Fox theme played over the Fox and Lucasfilm logos had been phased out. It’s a deliberate throwback that shifts the audience out of time and prepares them for a world that’s old and new at the same time, where characters who hang out in samurai robes all day can also pilot spaceships. Along the way, the music will also tell us who our hero is, by reprising the title theme when Luke first appears, and tell us of that hero’s longing for adventure. The moment in which Luke watches the binary sunset of Tatooine is well-photographed, but it’s the epic, swelling strings of William’s orchestra that tell us that Luke is destined for greater things.

The first time Lucas showed an edit of Star Wars to his film school buddies, it was with a temp score, and it fell flat. It’s easy to see why. The acting in Star Wars is fine, if deliberately simple. Alec Guinness is brilliant, because Alec Guinness was brilliant in everything, even shit that he clearly did not understand or care for, and Harrison Ford is at the peak of his dangerous charm here. But it’s the music that gives the film its emotional resonance. Its the music that holds its breath along with us as Luke reaches out through the force to line up that final shot in the trenches of the Death Star. It’s the music that makes us forget about Han Solo riding in to the rescue, as I do every single time I watch that moment.

So, for me, if Luke Skywalker is the heart of Star Wars, then John Williams’ music is the soul. How about you, Donald? What defines A New Hope for you?

Donald McCarthy: That’s a tough question. I guess if there’s one moment that encapsulates my experience, it would be the duel between Vader and Obi-Wan. It’s not the most exciting duel on a visual level, sure, but it felt like two titans, who had this massive history we only knew a small part of, meeting, lording over everything else. It established an epic scope all while being just an old man and a guy in a black costume meeting in a grey hallway.

And then they have a sword fight with laser swords. It’s a ridiculous concept that somehow manages to be the coolest idea in the world. As a 7 year old who loved knights and castles, seeing a sword fight with laser swords was mindblowing. The film went from awesome sci-fi to some weird form of fantasy. After that, anything could happen. Dragons could show up, magic could be used (and both of these happened, in some form), and God only knew what else. Star Wars is interesting because it establishes a genre, or perhaps even a lack of a genre, for the rest of the films. It’s not science-fiction and it’s not fantasy. It’s not even speculative fiction, not as it’s usually defined, at least, because it takes place in the past and is presented like history. So what is Star Wars? Is it fantastical space fiction? I don’t know.

What I do know is that it’s unlike anything else before or after. Not even The Lord of the Rings establishes as unique a world as Star Wars did. Lucas brought in tropes from all sorts of disparate places: medieval fantasy, religion, the Vietnam War, old sci-fi serials, and a gritty, very 70s, vision of his world. Lucas’ refusal to land his film in any world that feels even remotely familiar is what makes this work. To go back to The Lord of the Rings for a moment, that series takes place in a well developed fantasy setting, yes, but one that is very visually familiar to anyone who has read medieval fiction or older fantasy. Even the phenomenal A Song of Ice and Fire has this familiarity, too. I can think of no other epic that has as unique a world as that of the Star Wars universe. That’s why even when there’s a weak film (Attack of the Clones) it still works on some level since we’re deep in a fascinating universe.

As the first film in the series and the one that most closely follows the hero’s journey, I think it’s easy to assume Star Wars is the most straightforward of the films. It’s true to an extent, but I think what works is that none of the other films have the same structure. I’m sure many will have negative things to say about The Phantom Menace, but it’s the one that comes closest to the original yet it ends up reversing much of the expected narrative because Anakin’s hero’s journey is one that we know will fail, while the characters in the film treat him much as Luke is treated at the end of Star Wars. It brings a nice level of tension to the film.

It would’ve been really easy for Lucas to sell out and just keep remaking Star Wars again and again, a trap many of the shared universe comic films have turned into and something I desperately hope the Star Wars Disneyfied films don’t, but instead each film has its own feel, thus never diluting the original. I think that’s why it’s so easy to go back and watch the original Star Wars; Lucas never returned to the same well despite continuing the story and nothing non-Star Wars has been able to match it. It’s still as stand out today as it was so many years ago. When kids today are introduced to it they’re still in awe.

As they should be.

Lawrence von Haelstrom: You both are right about the economy of the narrative, and the fact that the same beats aren’t hit in every film. There’s so little time spent on exposition. A history is hinted at, a broader universe is suggested, but what we actually see is a series of action and adventure sequences. Your imagination is what make the bigger world. Obiwan Kenobi says a few words like, “Guardians of peace,” “Dark times,” and talks about betrayal and murder, and your imagination is on fire. The prequels were bound to disappoint if only because nothing on film could match the power of those brief flashes of our imaginations.

One of the defining things in Star Wars for me is the editing. There are three different credited editors on the film--Richard Chew, Paul Hirsh, and Marcia Lucas. Whoever was the driving force in the editing, I’m not sure. But the editing is brilliant. The Millenium Falcon escape from the Death Star scene is a well-studied one. A series of very quick cuts--TIE fighter across the screen, gun turret swivelling, a head turn, and so on--create a visceral momentum. The film is moving around and twisting you like a county fair Scrambler ride.

We keep mentioning the trench scene. I watched the movie again while I was working on my first response here, and, sure enough, I noticed something I hadn’t before in that sequence. The moment before Han Solo appears, this is the sequence:

Luke’s X-Wing moving across the screen

Darth Vader’s TIE Fighter and two others TIE Fighters moving towards camera

Luke’s face

Darth Vader working his controls

Insert of Darth Vader’s targeting display

POV Shot from Vader’s TIE Fighter (X-Wing is mimicking the movement previously seen on the display)

X-Wing moving across the screen

Luke Close up

X-Wing POV, flying down the trench

TIE Fighter targeting display

Darth Vader: “I have you now”

Vader’s hands on the trigger

TIE Fighters moving towards camera, Vader’s TIE fires, simultaneously a laser comes from the top right corner of the screen and the TIE fighter on the left side of the screen explodes.

Luke

Vader looks to his left, our right

TIE Pilot looks to his left and up,

Han Solo: “Yeeh-hooo!”

And we’re like, “What, Han Solo?! But, movie, you never showed us Han Solo was even here!” Traditionally, a film would have shown the Millennium Falcon first to establish it in the film’s geography. We have this very fast but steady rhythm of spaceship, character, spaceship, character, leading us to think this moment is entirely between Luke and Vader. Then all of a sudden, a new face. A face we already know we love. How he fits into the action at the moment we see him doesn’t matter. It’s Han! The next few moments, we quickly backtrack in our head to put him into the film’s space. Oh, he’s in the Millenium Falcon, that was he who shot that TIE fighter. Yay, Han! Go, Luke!

And I wrote all of that just to say that part is awesome.

Scott Waldyn: You’re absolutely right, Lawrence. Tight, rhythmic editing — seemingly intimate and personal between Luke and Vader. Tight framing. The trench run scene is intensified because of this tightness, and the walls only add to this confinement. There’s very little space for Luke to squirm around in, and as we saw in the first attempted Death Star trench run, on that rebel pilot’s targeting computer, the vertical lines measuring distance close in toward each other the closer the pilot flies toward the Death Star’s thermal exhaust port. Thus, the nearer our hero is to his objective, the tighter the confinement, the less space he has to wiggle away from Darth Vader’s quick trigger finger.

We can only hope that crazy old man Ben Kenobi knew what he was doing when he urged Luke to switch off the targeting computer and use the Force.

And going back to what Matthew said about the John Williams music, the strings, percussion, and horns only play to this tension. I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again — whenever I hear that trench run music, I get goosebumps. It’s panic-inducing, but it’s also proven the most fun for work commutes in rush hour traffic.

Aside from how perfect the tension is in the trench run scene, one of my favorite moments about it is right at the end, after Vader is knocked out of the trench and Luke fires off those proton torpedoes. It seems so simple and stupid, but does anyone else LOVE that exasperated gasp Luke makes?

I find it very touching and so very human. It’s the perfect epilogue to this crazy space adventure of a farm boy who becomes the galaxy’s biggest hero. In his moment of ultimate triumph, his reaction is to gasp out all of that worry, fear, and panic he’s been holding back. Audiences don’t see this in their heroes much, as it’s too human and lets the audience know the hero might not have been sure he could win. You wouldn’t see Batman gasp like that after he rerouted the direction of a bomb. But Luke does. And it’s perfect. Relatable. Sympathetic. It reminds us that he’s just like us in a way, and most importantly, I feel it’s a simple way of reconnecting this character to his roots, reaffirming us all that he hasn’t forgotten where he’s come from.

And as the Death Star gunner charges up the cannon, that mechanical whir seemingly emulating the path of Luke’s proton torpedo before it impacts deep within the Death Star’s core, we can lean back and gasp with Luke, too, and remember Tatooine and those T-16s and womp rats back home.

Matthew Guerruckey: I agree--that breath is one of the things that separates Luke from other, more overtly masculine heroes like Batman or even Han Solo. But those proton torpedoes, with their wriggling tails of energy, look pretty familiar from eighth grade Health class. Among the many other things that it is, Star Wars is also Luke Skywalker’s journey into manhood, completed only when he drives his phallic aircraft deep into a trench and “lets go”, releasing sperm-like bursts of energy into the tiny opening of the breast-shaped space station, collapsing with orgasmic relief. I mean, it’s far removed from Barbarella, but the symbolism is there.

But our praise of the editing in A New Hope is as good a time as any to bring up the Special Edition edits. Before we began this project, I was neutral on the Special Edition changes, primarily because it had been so long since I’d watched the original version of A New Hope. But for this rewatch, I dug out the 1995 VHS re-release (“For those who remember, for those who will never forget … ”) and watched that, as well as the 2006 Special Edition DVD. I’d never watched the two versions so closely before, and that proximity made the changes, especially to the editorial and narrative flow of the film, stand out. George Lucas very nearly ruins his own classic movie.

The theatrical version of Star Wars, which we all loved for two decades, moves at a brisk clip. By constantly inserting extra shots, even if they only last a few seconds, the flow of the editing slows down dramatically, throwing the timing off, making the movie feel slower, heavier. The new introduction to Mos Eisley adds nothing to our understanding of the place, and allows only for some of the unnecessary slapstick that would come to define the prequel trilogy. We’ve just been told by Ben Kenobi that Mos Eisley is the most dangerous place in the world--yet now, the first thing we see of it is a Jawa getting tossed around, comically, by a space camel. We’re introduced to Jabba the Hutt in a scene which stops the film cold, with horrible computer graphics and silly Boba Fett fan-service. Even worse, the scene is completely redundant. All of the information that we get from Jabba we already know, because of the scene with Han and Greedo in the Cantina.

And, while we’re on the subject of Greedo: Han shot first. Of course he did. Han shooting first is the only reason for the existence of the scene. It’s our first glimpse of who Han really is, and that scene plants a seed of doubt in the mind of the audience. We’ve just seen Luke and Obi-Wan, two people we’re sure we can trust, hire this guy, and now he murders a creature in cold blood, to save his own neck. It’s proof of just how far Han will go to save himself, which is why we’re all the more surprised when he risks his life to save Luke at the end of the film. If Han is only acting in self-defense, then he’s merely a gunslinger, and not the notorious scoundrel that the narrative needs him to be. It neuters Han Solo, and it neuters the story.

I’m sure we’ll address the Special Edition edits again, especially when we get to Return of the Jedi (I’ll be watching my VHS versions again for that, to avoid “Jedi Rocks” and glowing Hayden Christensen), but they highlight a bizarre facet of Star Wars fandom--that in loving these films, we have to accept the eccentricities of their creator, who at times seems pathologically unsatisfied with his work.

Donald, does the Special Edition of A New Hope work for you? Do you find the flow of it any different than the original version?

Donald McCarthy: That’s a good question. I didn’t find that it detracted from the flow previously, but I sure can see it now. When the Special Edition came out I had just seen the original and was excited about the fact that when I saw it next it would now have more. What that more was didn’t really matter to me. My opinion didn’t change much when I was 15 and the DVD was released; more Star Wars is awesome. It’s almost like you’re getting to watch the film for the first time again.

Now that time has passed, and we’ve had yet another Special Edition with the Blu Rays, my opinions are much more mixed. Many of the recent additions are ridiculous, such as Darth Vader shouting “NOOOOOOOOO!” as he picks up The Emperor at the end of Return of the Jedi, and Lucas trying to have the best of both worlds with the Han and Greedo scene. It seems like we’re at the point where Lucas is saying, “Actually, they shot at the same time, guys!” If Lucas still had his way they’d probably shot at the same time and have the blaster bolts hit each other. I simply can’t fathom why he made this change.

I don’t mind him cleaning up some of the special effects, such as the better quality of the X-Wings approaching the Death Star. But the Jabba scene? Is there any reason for that? It was a correct cut originally and there was no need to put it back in. It adds nothing and it looks awful in the first Special Edition. Plus, Han stepping on Jabba’s tail breaks the story. Jabba would never tolerate that. I guess it’s a funny gag in the moment, but it takes away from Jabba’s character.

Jabba the Hutt, as he appears in the Special Edition of Star Wars (Image © Lucasfilm).

The background additions, such as the Imperial shuttle in the desert, don’t bother me much and some are pretty neat. There are some that are too cutesy, such as a few of the droids interacting during the entrance to Mos Eisley.

In general, I guess I’m torn on the changes. I’m not opposed to Lucas making changes as some are. I’m fine with a director redoing work. I know some argue that once it’s out it’s out, but this goes against centuries of examples of artists doing the opposite. I just find that some of the changes he made are bizarre.

Speaking of seeing a different version of A New Hope, I’m curious how people view it now that they’ve seen the prequels. There’s some awkwardness simply because the prequels are such different films with very different goals. To jump to a different example, when you watch Alien after seeing Prometheus you have a slightly different experience, but the two films aren’t all that tethered so the fact that they were made thirty years apart doesn’t make the viewing experience all that different. Since the prequels had such a different look and such different effects, going from Revenge of the Sith to A New Hope is going to end up resulting in some raised eyebrows. I often wonder if that is what drove Lucas to make changes to the original films so that the special effects aren’t so different. I’m not sure there’s really any way to pull that off, however.

On a character level, despite the prequels’ flaws, I do find that some scenes resonate more, such as Obi-Wan giving his “certain point of view” speech to Luke and Darth Vader commenting that he hasn’t sensed a feeling in a long time (him ending that line in mid-sentence is one of my favorite touches). Then there’s Darth Vader saying the Force is strong with Luke and you’re sitting there saying, “Oh, you have no idea buddy.”

So how about you guys? Have the prequels changed your viewing of A New Hope?

Lawrence Von Haelstrom: Star Wars, aka A New Hope, is my favorite movie of all time. I know no other movie as completely as Star Wars. It’s like a favorite song where you know every part so well you can recreate it entirely in your head. For me the prequels, and even to some extent the sequels, are addendum that can be taken or left depending on my mood. I’ve tried watching A New Hope as a subsequent episode to the prequels, and, like Donald said, there are some fun, new readings. Obi Wan and R2D2’s initial exchange of glances on Tatooine changes meaning. Without the prequels, Obi Wan looks at R2 with simple curiosity, while R2 trembles in fear. In context with the prequels, R2 is trembling with excitement seeing his old friend while Obi Wan gives him a conspiratorial nod. “I see you, little man. Let’s just stay cool for now,” that nod now says. But for the life of me, I still can’t imagine Hayden Christensen’s Darth Vader behind the Darth Vader mask. When Obi Wan says Darth Vader was a pupil of his before Vader turned to evil, I still see my own flash of imaginary backstory before I remember the prequels. (And I actually like the prequels!) So, for such a familiar text, the prequels can provide a fun new way to watch Star Wars. But they haven’t fundamentally changed how I see the film.

As far as the Special Edition changes go, I don’t see them as sacrilege to a sacred text. Philosophically, I’m a post-modernist who doesn’t believe in an authoritative text or authoritative reading of a text. And what that non-pretentiously means is that my opinion is, “Oh, fuck it. Whatever.” Do the changes improve the movie? Honestly, not really. Are they the equivalent of Isis taking a sledgehammer to ancient Assyrian sculptures? Eh, no.

And about Jabba the Hutt: I first figured his uncharacteristic behavior in the Special Edition was because he was still working his way up in the thug game. By the time of Return of the Jedi he was Avon Barksdale, but at the time of A New Hope he was still off-brand. But then in The Phantom Menace we see him lording over the Boonta Eve Podraces, so that kills that theory. So my guess now is that after Phantom Menace maybe he tried to expand his empire too fast too quickly, maybe he was even snitched on by Watto or something, and he lost everything. At the time of A New Hope he’s rebuilding, then by Return of the Jedi he’s at the top of the game again. It’s a rise-fall-rise story. Makes sense, right? Right?

Honestly, one of the most fun things about Star Wars is making up excuses for its flaws. I go back to my repeated point about how it triggers the imagination. There’s just so much there.

Scott Waldyn: The prequels are dead to me, as are the Special Edition edits. The way I see it, these changes and sloppy “origin stories” are piss-poor pieces of propaganda put out by the Galactic Empire to damage the credibility of the Rebel Alliance. And I won’t fall for it. The Imperials, George Lucas and Disney, can have their records, but I will choose my own.

This goes back to something I was scratching at earlier — the beauty of Star Wars. When I was a kid growing up in the 90’s, the Star Wars machine was pumping out video games, books, toys, expanded universe toys, and encyclopedias like crazy. Every half a nerd and his/her mother was contributing to the Star Wars universe, co-creating in this gargantuan sandbox. While you constructed yours in the confines of your own play room, someone was building an entirely different timeline halfway across the world, and the only definitive thread each timeline kept was the core three films. These were the only foundational elements that each kid incorporated into his/her Star Wars Bible, and by the time the prequels came out, it was too late for anymore editions. There were already hundreds of books and dozens of video games. Many, many creators had mined that well for more stories, and those who had grown up with Star Wars were previously accustomed to accepting/rejecting tales based on whether or not they enjoyed said tales. George Lucas lost his godhood the moment he opened up Mount Olympus to the creative fans, and by the time The Phantom Menace hit theaters, it was anyone’s game.

Having said all that, the prequels have not had an effect on my reading of Star Wars: A New Hope. Like that 2001 Tim Burton Planet Of The Apes film, Alien Resurrection, and any of the Highlander sequels, they’re not real. They’re just nightmares, distortions, and pieces of propaganda put out by enemies of the New Republic. In my world, Jabba the Hutt was too high and mighty to slither around on the floor and plead with Han Solo. He was better as a shadowy figure with a powerful name denizens of Tatooine threw around. We didn’t have the street cred to meet him when I was a kid, nor would we, until Return Of The Jedi. And that’s the way I like it.

Call me a curmudgeon, but I won’t be changing that stance any time soon.

Matthew Guerruckey: Based on that passionate reaction to the prequels, Scott, I can’t wait to discuss Revenge of the Sith with you later in this series.

But, to wrap up our thoughts on A New Hope, this is a movie that we’re obviously all familiar with, so I wonder: what did you take away from this viewing?

My chief takeaway this time, after going so long between viewings of the original cut, is how well it holds up as a piece of filmmaking. It’s nice to think of it as a classic that holds its own against films like The Wizard of Oz or It’s a Wonderful Life. I like to think that in another seventy years people will still be watching it, and reacting to it with the same joy that I did when I first encountered it. It’s nice to think of a message that hopeful living on.

What was your takeway this time, Donald?

Donald McCarthy: I was impressed how well the tension in the film holds up. For a family film, it’s practically a thriller at times. I can’t imagine ever watching the trench run and not being terrified for Luke’s wellbeing. I can’t imagine not getting chills the first time Darth Vader walks onto the Tantive IV. I can’t imagine not breathing a huge sigh of relief when Han Solo shows up at the end. I certainly can’t imagine not feeling total despair when Obi-Wan Kenobi is struck down.

I can’t think of many other films that have this affect on me. There are a couple of David Lynch films that disturb me no matter how many times I watch them, but otherwise most movies do lose their effect if you watch them too many times. Not so with A New Hope.

I’m also impressed with how well put together the film is considering how much of a disaster it could’ve been. How Lucas pulled it off, I’ll never know. I’ve read that he got sick a number of times while filming and that Alec Guinness often cheered him and the rest of the crew up when times were tough. The special effects, the sets, and the direction are all outstanding in a way that’s almost unfair when you look at the circumstances the film was being made in and how many of the Hollywood producers thought the film would be a joke. Lucas gets a lot of shit, some fairly but much unfairly, I think, now, and some of the more controversial films and changes he’s made overshadow what an amazing accomplishment A New Hope was.

And it shows in the film itself, which is why it still works and why it’ll always work. I have no doubt that kids twenty, thirty, forty years from now will still be enjoying the original Star Wars (unless global warming wipes us out).

What did others take from it this time?

Lawrence Von Haelstrom: This time around I was hyper-focused on the editing, and I talked a little about that earlier.

But the most recent time before that was on Christmas day when I watched it back to back with The Wizard of Oz. And by doing that the parallels between the two films became amazingly obvious. While Star Wars is certainly not a simple retelling of the Wizard of Oz in outer space, the film packs in more Wizard of Oz nods than you realize. There are straight parallels--Scarecrow, Tinman, and Cowardly Lion sneak into the very Death Star-like Witch’s Castle by dressing as the very Stormtrooper-like Witch’s Guards. But that are more subtle parallels in tone and imagery. Matthew talked about the very linear narrative of Star Wars. While there is no literal Yellow Brick Road, Luke’s journey is as rigidly delineated as Dorothy’s. Each event leads directly to the next. For original audiences of Star Wars, knowledge of the Wizard of Oz helped make the totally alien galaxy far far way more welcoming. R2D2, the non-verbal, surprisingly brave and clever little friend, is a robot Toto. C3PO and Chewbacca visually remind us of Tinman and Cowardly Lion. (Even if their personalities are different.) We’ve been on amazing journeys like this before and Star Wars smartly relies on our familiarity with those stories to make it all work. What’s very interesting is that a movie with so many references to other films has become such an omnipresent reference point itself. Ultimately, the sincerity and eager energy of Star Wars make it’s total effect so much more than the sum of its allusions. It’s just brilliant and timeless, endlessly fascinating, and totally fun.

And, okay, so we all love this movie. Anybody want to play Devil’s Advocate and try to explain why it may not be timeless?

Scott Waldyn: I don’t think I can give a passionate case for Devil’s Advocate. I don’t even want to try. This film is a gem, and to those who disagree, I say, “Your path to the Dark Side is now complete.”

As for my chief take-away, I believe all the answers you seek can be found here.

The Force will be with you, always.

Join us in May for our discussion of Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back, with Taras D. Butrej. Don’t forget to share your own memories, observations, and critiques of A New Hope in the comments below!