There, drunk in a bar where no one was watching and no one would care, I asked Tyler what he wanted me to do.

Tyler said, “I want you to hit me as hard as you can.”

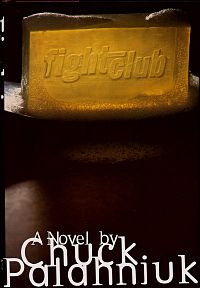

-from Fight Club by Chuck Palahniuk

Fight Club is a disjointed novel told in swift, brutal jabs of black humor–at once a tribute to and a mockery of masculinity. Chuck Palahniuk wrote the book as a commentary on the basic need, in men, for ritual and tradition that is stifled by modern consumer culture. The book was a moderate success, but became much more well known in the wake of a controversial film adaptation starring one of the biggest stars in the world. The film bombed at the box office, but had a huge second life on DVD (one of the first movies to really take advantage of the medium to build a fan base). A few years after its initial release Fight Club was considered a cult classic and pop culture phenomenon, prompting men across the world to ask themselves,”what would Tyler Durden do?”

The novel focuses on an unnamed narrator who suffers from insomnia and attends support groups for diseases he doesn’t have to feel some kind of emotional release in his empty life. While at one of his groups he meets a fellow faker, Marla Singer, a burnout who makes the narrator all the more aware of his deception. Soon after Marla comes into his life the narrator meets the charismatic and mysterious Tyler Durden. When the narrator’s condo is destroyed by a bomb, planted while he was away on a business trip, he goes to live with Tyler is an abandoned house on the edge of town. Tyler’s only condition to let the narrator stay with him is to challenge him to a fist fight, the first of many fights, which culminates in the founding of Fight Club–a kind of support group with fists. Through fighting the narrator finds peace, but Tyler is not content. He begins to turn Fight Club into a terrorist organization whose mission is to destroy anything that is reflective of the corporate emptiness of modern life. While attempting to learn Tyler’s ultimate goal the narrator must face a more startling truth–that he actually is Tyler Durden.

The book began as a seven page short story (which would later become the sixth chapter of the novel), written by Palahniuk as a way to pass a boring afternoon at an office job. The story was published in the small-press anthology The Pursuit of Happiness. Palahniuk spent only three months fleshing out the story to a full-length novel, and sold it to W.W. Norton for what Palahniuk referred to as “kiss-off money”, a sum so small that the author is meant to feel insulted and walk away from the deal. The book was a modest hit, gaining mostly positive reviews and winning the 1997 Pacific Northwest Booksellers Award.

Before the book was published galleys were sent to film studios to determine interest in an adaptation. Most of the studios passed, and it’s not hard to see why. While undeniably funny and smart, Fight Club also contains a disturbing amount of violence, and an underlying message just ambiguous enough to make it a risky project for any film studio. Producers Josh Donen and Ross Bell were among the few that believed that a film adaptation could work. They hired (but didn’t pay) actors to read the script, then shopped that tape around town. One of those tapes was sent to Laura Ziskin, head of Fox 2000, who loved it and bought the film rights from Palahniuk for $10,000.

The script was adapted by Jim Uhls, a UCLA film school graduate with no prior writing credits, though once director David Fincher came on board he brought in Andrew Kevin Walker, who had written Fincher’s feature debut film Seven, for some uncredited re-writes. Fincher was a music video vet whose first two films, the aforementioned Seven and the paranoia-fueled thriller The Game, had given him a reputation for edgy, dark fare that was tightly paced and stylish.

Brad Pitt as Tyler Durden (Image © FOX)

Many actors, including Russell Crowe, were considered for the all-important role of Tyler Durden. Fincher’s previous experience with Brad Pitt on Seven helped steer the part toward the star. Pitt was just coming off the failure of Meet Joe Black and was anxious to shake up his teen-idol image, as he had previously done with his twitching, grotesque performance in Terry Gilliam’s 12 Monkeys–a role that would bring his first Oscar nomination. Pitt was signed to the film for the astronomical sum of $17.5 million. The addition of one of the biggest movie stars in the world and the fastest-rising director in Hollywood transformed Fight Club from an afterthought to a huge production burdened with expectation.

Edward Norton was brought in to play the narrator. Norton had received an Oscar nomination for his breakout role in Primal Fear (where he played, of all things, a kid suffering from multiple personality disorder). Both Pitt and Norton are perfectly cast. Tyler Durden is a creature built entirely of cool, a teenage boy’s idea of the ultimate rock star/action hero. Hiring the ultimate movie star to play him brings the character to vivid life, and allows Pitt to deconstruct his heartthrob image. Freed by the role, Pitt gives an energetic, hilarious performance. Norton is equally good at capturing the narrator’s agitated longing.

Fincher’s trademark attention to detail makes him the perfect director for the adaptation, and reflects the insane digressions and hyper-detailed history lessons of Palahniuk’s narrator. Fincher uses quick editing and CGI to keep the world of the film balanced no matter how fantastical the story becomes. Fincher insisted on the use of voice-over narration, a technique that infuses the film with the same casual, witty vibe of the novel. Without the wry, calm tone of Norton’s voice-over, Fight Club would be an unbearably dark and violent film. But with the narration intact we are able to see Palahniuk and Fincher’s work for what it is: a comedy.

And, in spite of its trenchant observations of consumer culture, a comedy is all Fight Club really is. The greatest mistake made by both the harshest critics and the most devoted fans of the film is taking it much too seriously. Fight Club is not, as some feared or hoped, a call to arms to a generation of disaffected youth. Tyler Durden is the product of a diseased mind, and even if that mind has been corrupted by consumer culture, the destruction of that culture will do nothing to end that disease. At the end the narrator realizes that his drive to create Fight Club and Project Mayhem was not based in lofty idealism, but his fear of his feelings for Marla. As with any mental disorder, the coping mechanism (Tyler) appears as a crutch during a time of great stress and change, but then becomes overwhelming, at which point the coping mechanism itself is the final roadblock to wellness. This is as true in the film as it is in the novel, though Tyler’s end goal in both works is very different.

Both the novel and the film begin with Tyler holding the narrator hostage on the top of a building that Tyler has rigged to explode. In the book the purpose of the detonation is to cause the building to crumble onto the museum across the street:

The last shot, the tower, all one hundred and ninety-one floors, will slam down on the national museum which is Tyler’s real target.

“This is our world, now, our world,” Tyler says, “and those ancient people are dead.”

In the film the purpose of destroying the building is to disrupt the services of credit card companies that are based there, thereby zeroing out the credit scores and making all consumers equal again. Both plans are absolute bullshit. Anybody who has seen the demolition of a building knows that they usually pancake down rather than topple over in the way necessary to achieve book Tyler’s plan. As for movie Tyler, even destroying the paper records in the credit building, and any computer equipment located inside, would still certainly leave dozens of branches and servers located elsewhere. Both plans are insane, the work of an adolescent mind lashing out at a world it feels rejected by with an empty, destructive gesture. Allowing the resolving thread of the plot to hinge on such lunacy is a major problem, both in the book and the film.

Likewise, the major reveal of the story, that Tyler Durden is a “split personality” creation of the narrator’s dissociative mind is a lot to swallow. And even worse, the twist is telegraphed far in advance, perhaps out of a sheepish acknowledgement of its basic silliness. In the book, Tyler first appears as the narrator lies on a nude beach while on vacation, in a scene so dreamlike and bizarre that it doesn’t feel real for a second:

Tyler was naked and sweaty, gritty with sand, his hair wet and stringy, hanging in his face.

Tyler had been around for a long time before we met.

The first time we encounter Tyler in the film is via one-second flashes during the narrator’s bleary-eyed workdays and nightly trips to support groups, a clever visual touch that echoes Tyler’s night job as a projectionist, where he splices single frames of pronography into family films. The narrator also passes Tyler on an airport conveyor belt at the same moment he says in voice-over, “If you wake up at a different time, in a different place, could you wake up as a different person?” Not subtle, especially on a rewatch.

Pitt and Norton (Image © FOX)

The central problem at the heart of the novel and the film are the same. Both are great-looking houses built on shitty foundations. No matter how brilliant the prose or the performances, each work is going to have to account for the fundamental weaknesses in the story. These flaws keep both the book and film from developing into the black comedy classics that they should be.

By the end, Palahniuk’s Fight Club is an incoherent mess, but the adaptation wraps up swiftly enough to retain some of the acerbic core it began with. The first half of Fight Club is one of the greatest dark comedy films ever made, but saddled with an inevitable slide into mediocrity, and either unwilling or unable to change that trajectory, it too limps to an unsatisfying conclusion.