The zebras are looking at me. Posters of zebras in all these zebra poses paper the walls, the zebras and a poster of Eddie Vedder. Three stuffed zebras lay at the foot of the bed, and a black-and-white striped comforter half-covers my body. Nikki loves zebras. And Eddie Vedder. She’s always trying to get me to grow my hair long, like Vedder, and thought The Shit Stains should cover either “Even Flow” or “Rearviewmirror.” I told her she’d never hear crap Grunge coming from my ax, but secretly I learned both songs. Including the solos.

I’m still in my clothes, and two egg-sized lumps are throbbing on the crown on my head. I throw my arm over my eyes to keep the daylight away. When I remove it, the zebras frown and I frown back. Vedder is staring so I flip him the bird. This is the first time I’ve woken up in Nikki’s room, in Nikki’s bed, and not been with Nikki. She lives with her mom, but her mom is cool with me staying over. Her mom actually likes me, which is unusual for parents. Nikki’s dad, like mine, was never around. I met him once when he stopped by her mom’s place to drop off a birthday gift for Nikki—a beat-up stuffed puppy with a bow. The old man was drunk and told me to keep my grubby hands off his daughter.

I finally get up and walk to the window, allowing my eyes to adjust to the daylight. Outside, gray clouds squat in the sky, and when a spit of sunlight tries to poke through, the clouds beat it back. Gusts of wind toss empty trash cans through the tenant lot, nearly bowling over a guy with a fleece scarf wrapped around his face like a bank robber, scraping the ice from the windshield of a dented black sedan.

The bedroom door opens and Nikki comes in wearing flannel pajama bottoms and a pink tank top, carrying two cups of coffee. She hands one to me and then yawns and stretches. Goddamn, she’s beautiful when she yawns and stretches—more beautiful than she’s ever been.

She sits on the edge of the bed and begins tapping her foot. “Roach called last night to tell me you were passed out beside the dumpster outside The Cask. You could’ve frozen to death, Pete.”

“Why did you do it, Nikki?”

“You could’ve died.”

“Can I bum a smoke?” Nikki tosses me her pack of menthols and a yellow lighter. Outside, the wind howls past the window and pounds the siding of the old house. “Is C.R. Little going to flip out if he finds out I’m here?”

C.R. Little is the professor at the community college, the guy who she’s cheating with. His name is Christopher, but people call him C.R. because he writes poetry under the name C.R. Little. That says it all, doesn’t it? Only assholes and rednecks use their initials. And if you don’t believe me, check out one of his books. Nikki has a couple of them, and in every author photo, he has one hand scratching his chin like he was in the middle of some big fucking thought and interrupted when the picture was snapped. This chin-scratching asshole stole my girlfriend!

“Pete, are you listening to me?” Nikki snaps her fingers in front of my face. “It was C.R. who helped me carry you to the car and then up the stairs to my room. Instead of ragging on him, maybe you should thank him.”

“Your mom must’ve been impressed, seeing he’s her age and everything.”

“Go to hell.”

“I was saving money to buy you an engagement ring, Nikki.” It’s the truth. I started saving twenty-five bucks from each paycheck so I could buy her this pinhead-sized diamond—one-tenth of a carat. I’ve saved a little over four-hundred bucks I keep in a CD case in my dresser.

“You’re crazy, Pete.” Nikki stands up and walks to the window, her back to me. “One minute, you want to be a rock star and drink all the time then the next minute you want to get married. We’re too young, Pete. Christ, I just graduated high school last year, and you should be finishing in June. You don’t know what you want, and I don’t want to wait around for you to figure it out. Listen, I’m sorry, Pete, but it’s over.”

The room is so still and quiet I can hear my blood rushing through my head. My stomach lurches, and I feel like I want to puke up those two words. It’s over. It’s official. I hear them again and again, like the note the hippie band’s guitarist kept bending.

“I got to go.” I get up and grab my army field coat from an armchair stacked with stuffed zebras, the ones who didn’t quite make the cut for the bed—the B-side zebras.

As I start toward the bedroom door, Nikki blocks my path. “Are you going to be all right?”

There are so many things I want to say to her. Too many. We spent three years together and, suddenly, it’s over? Done? What the hell am I supposed to say?

“I’ll be fine.”

“Are you sure?”

“I’m fine.”

With her head down, she steps aside and lets me walk out. I’m hoping she’ll stop me, plant one on my mouth, rip off her shirt and tell me it’s all been a big mistake then beg for my forgiveness, beg me to touch her and take her back. But the door closes.

It’s over.

Before plunging into the pounding wind, I put on my wool gloves and zip up the field coat as far as it will go, pulling it over my nose. I slip my black watchman’s cap over the pulsing knots on my stubbly skull. Outside, the bone cold slaps me. I start down the icy sidewalk spackled with sand and rock salt. On the other side of the street, there’s a hatchback with its front end crushed, plopped in the snowy front lawn of an old ranch house.

I shiver, sigh, and begin the two-mile trudge to my brother’s house, where I live with him, his wife Pam, who for the past year has been patiently waiting and not-so subtly hinting for me to move out, and my three-year-old nephew, Eddie. I’m the proverbial third wheel: the fucked-up kid brother who lives in the attic. No doubt, I need to get the fuck out of Rhode Island. While Pam clearly wants me out of the house, Dwayne is pretty cool about it and doesn’t say much. He’s a tattoo artist—covered in them himself—and does mine for free. I have thirteen tats now: six on each arm, and a kick-ass Chinese dragon breathing flames down my shoulder blade. When Dwayne did my first one, a small anarchy sign on forearm, I was sixteen, which is technically illegal without a parent’s consent, but my mom didn’t care. She has a Hell’s Angels skull tattooed on her ass cheek and showed us when she was drunk one night. Most of the time, when she was still around, she was out partying with her boyfriends so it was just Dwayne and me at home. It seems like it was always Dwayne and me at home when we were growing up. But he’s a great guy and kick-ass older brother, and you’re going to love him.

This will be the first time in three days I’ve been home, and I’m going back a different person—a guy without a girlfriend, or a guitar, or much of anything besides a headache.

When I walk in, Dwayne is sitting on the living room couch, hunched over the coffee table, pulling the stems and seeds from a bud of weed. With the exception of the first five or ten minutes when he wakes up, Dwayne is baked all day, every day. Me, I’m not into weed. If I smoke it, I end up eating peanut butter straight from the jar for forty-five minutes, having a goddamn panic attack, and then going to sleep. No thanks. I’ll stick to booze.

Dwayne glances up, brushing his long brown hair out of his eyes. He nods. I nod back, holding my hands over the heating pipes by the stairs.

“You look like you’ve been fucked by a truck,” Dwayne says and reaches in the pocket of his flannel shirt for his rolling papers. “How did the gig go the other night?”

“For forty-five seconds, we kicked ass.”

“That’s a quick set.”

I take off my boots and place my wet socks on the radiator. “Nikki and I broke up.”

“I’m sorry, Pete.” Dwayne starts spinning the joint. “Are you all right?”

“I’m fine.”

He doesn’t press me for information. My brother is the type of guy who smiles and nods and shrugs a lot, but doesn’t say much. Although he’s four years older—our old man bolted when we were both too young to remember—Dwayne has never tried to pull the father-act with me.

While my old man was never around, there was never any shortage of dudes staying at the house. To put it kindly: my mom got around. And she had a thing for bikers, hence the ass-tat. The longest she dated one guy, on and off, was three years. That guy was Ron Greene—some greasy jerk from Fall River who had a caterpillar mustache and hard eyes. Ron did some prison-time and liked to use it as leverage when he was threatening to beat the shit out of you with a belt. But my lasting memory of Ron Greene came in the form of a blood stain.

I was in the third grade, and my mother and Ron threw one of their weeknight blasts at our two-bedroom place in Cranston. Ron and his buddies were in the kitchen that night, all coked-up, and according to my mother’s story, they were playing Russian roulette—whether or not that was really the case remains debatable. I remember being in the dark bedroom I shared with Dwayne, trying to get to sleep, when the gun went off and my mother screamed. Terrified, Dwayne and I ran into the kitchen and found Ron’s brains painting the wall, small chunks of skull on the floor, and his buddies running for the door. I still have nightmares about it, about that image of Ron’s head blown apart. Even now, telling you about it, I want to puke.

Afterwards, a social worker showed up at our house and almost took Dwayne and me away from my mother, but for whatever reason, it didn’t happen.

Dwayne exhales a cloud of smoke that settles in front of the television. “Are you working today?” He coughs and takes another hit and coughs.

“Four o’clock.” I shake my head. I almost forgot I had to work, and the thought of standing behind a counter at Cumberland Farms, selling cigarettes to the guys from the halfway house is making me sick. “I should quit.”

“Then what?”

“Then I’m unemployed.”

“Then how are you ever going to find your own place?” Dwayne flips through the channels, stopping on a documentary about some underground society of New York City dipshits who think they’re vampires, getting their teeth capped to look like fangs and swilling each other’s blood. Vampires, flannels, hippies—I fucking give up.

“Maybe I’ll tell my boss I’m going to become a rock star and finally get the hell out of this state.”

“Tell me where they’re hiring rock stars,” Dwayne says. “I’ll apply, too.” Like me, Dwayne understands the importance of jamming on the guitar. In fact, he’s the one who taught me to play. Since he was in high school, Dwayne has played in a handful of bands in the Warwick-area, one of which played at The Rocky Point Palladium a couple of years ago, opening for a Led Zeppelin tribute band called The Houses of the Holy.

Pam comes strolling in from the kitchen, eating scrambled eggs off a Spiderman plate. Eddie is behind her on his hands and knees, pushing a yellow plastic dump truck and making dump truck noises. “Goddamn it, Dwayne. How many times do I have to ask you to get high in the bedroom? The smoke isn’t good for Eddie.”

Dwayne picks up Eddie and bounces him on his knee. Eddie puts his arms in the air and starts cracking up. “The smoke isn’t good for Marty either, babe.”

“Mah-tee, Mah-tee,” Eddie yells. Marty is Dwayne’s pet iguana, and he and Eddie get all charged up over him. I like Marty, too. He’s badass.

“Here’s another idea.” Pam shrugs. “How about you stop smoking weed every second of your life?” Then she turns to me. “What’s this I hear about you moving out, Pete?”

I shrug. Believe me. I’d love to have my own place—preferably somewhere warm—where I can do whatever the hell I want. If I want to walk around my place naked, take a crap with the bathroom door open, or rub one out in the kitchen, no problem.

“How did the show go the other night?” Pam asks, punching me in the shoulder.

“The band broke up.”

Pam covers her mouth. Although you’ll never see her on a cover of some fancy magazine, Pam is foxy—pale-skinned and dark-haired, wide-hipped with one of those large smiles that make other smiles look small. “I’m so sorry, Pete,” she says, and I know she means it. She works third-shift as a nurse, and I can picture her with the patients, smiling or telling them she’s sorry, and meaning it.

“Where is your ax?” Dwayne asks.

“I smashed it. I guess I’ll have to play yours until I can afford a new one.”

“Not unless you want your hands cut off.”

Two years ago, my brother hit a scratch ticket for four grand and bought a mint 1954 mahogany-top custom Les Paul, otherwise known as The Black Beauty. It’s the guitar he plays on-stage with his current band, which plays Grunge covers a couple of nights a month at the Providence bars and clubs, and no one is allowed to touch Dwayne’s guitar. When he bought The Black Beauty, Pam freaked out because they were broke at the time. And while Dwayne adores that ax and she knows it, whenever they’re strapped for cash, Pam will suggest hocking it, and Dwayne will give her a look like a doctor snapped on a rubber glove behind him.

“Do you like my truck, Uncle Pete?” Eddie holds out the dump truck.

I take it from him and turn it over in my hands. “That’s a rocking truck.” I decide I only want to talk to Eddie. He isn’t going to get any deeper than his dump truck will let him dig.

Then Pam asks, “How’s Nikki?”

I hand Eddie the truck and turn up the stairs. My head hurts and I’m nauseous and tired and want nothing but to sleep for a long, long time. “I’m fine,” I say then book it up the stairs.

My mattress is old and ratty, and when I lie down, I sink like a wheel in mud. I don’t have a box spring or a bed frame, and due to rotten insulation, the floor in the attic gets so cold in the winter that Nikki can’t walk on it without socks. I used to tell her that I’d buy an area rug, and I even went to a few yard sales, but I never found anything. I guess I never looked too hard.

Like most attics, the room was built to be a storage space, not a bedroom, and I didn’t originally intend on staying here more than a couple of weeks. After I dropped out of high school last June, my mom moved to South Dakota with a biker named Peddler, a guy with two teardrops tattooed on the side of his face. Apparently, Peddler had a friend who owned a diner in Sturgis and promised them both work. At the time, I was living with my mom, so when she left I shacked up with Dwayne and Pam, thinking I’d soon get my own place, and after she graduated high school, Nikki and I would move in together.

I was wrong.

Even working full-time as a clerk, I’ve never had the money for my own place. And despite the countless sticks of incense, plug-in air fresheners, and a bowl of potpourri Pam bought me, a rank musty smell mixed with my smelly laundry clings to the wood in here. The smell shocks you a bit when you enter, but like most things, after a while, you get used to it.

But it’s not a bad room. The ceiling hangs low, but I’m short—about five-feet six, in boots—so it’s not too bad. The far wall slants, and on it I’ve tacked up a poster of Guns N’ Roses with the guys in the band decked in leather and denim, flashing their tats and bad-ass bandannas. If your band is on a poster, you know you’ve made it as a rock star. When people ask me why I quit high school and why I didn’t want to go to college, where some dipshit with a degree would tell me what to learn so I could get trapped in some suck-ass job where I’d make a decent living and look forward to my high-fiber shit each morning, I tell them the truth: I want to be a fucking rock star, a rock star who will someday be on a poster. I love to imagine myself on a poster tacked to a slanted wall. It’s like becoming a god.

As I lie here on my crappy mattress, my head pounding, and listen to G N’R’s Use Your Illusion II on my Walkman, I start imagining my funeral, which is something I do when I get depressed. For starters, I always imagine that I die young—at twenty-seven—and, of course, an international guitar legend. My funeral will be held at Lupo’s Heartbreak Hotel in Providence, where Nikki and I once saw White Zombie before they got big. I want a smaller venue, something intimate.

Now picture this: there will be a closed casket, center stage, with a red spotlight on it and a black curtain as the backdrop. As the crowd walks in, and each person is handed a six-pack, they’ll be looking directly at my casket. Guns N’ Roses will play two sets, a mix of their tunes and some covers of the songs I’ve written, like “Wasted on Date Night” and “Bite Me”. In between sets, some of the people closest to me—mainly Dwayne and Pam and maybe Nikki—will tell sappy stories about me doing nice things that will make everyone in the crowd misty-eyed, wiping snot on their sleeves. No tissues though.

As soon as everyone starts crying and the whole thing is in danger of getting drenched, Axl will scream into the microphone and the band will rip into “Get in the Ring” as Axl calls out Bobby Downs and C.R. Little on my behalf. Then it’ll close with “Rocket Queen,” and when the tempo slows at the end of the song, and Axl sings the part about standing all alone, all the lights on the stage will go out, except for the red spotlight still pointing at my casket. Using some elaborate system of pulleys and wires, my corpse—dressed in jeans, my army field coat and my black Pantera T-shirt—will descend from the ceiling. I’ll make sure that the mortician leaves both middle fingers up as my corpse is lowered to the stage. Everyone will go nuts, screaming and cheering and throwing their empties at it.

I can’t understand why anyone would want a weepy, whiny funeral. With tissues. Sleeves, I can understand. But not tissues.

Thinking about dying makes me a little anxious, so I stand up and start pacing. In the corner of the room is an empty guitar stand, which less than forty-eight hours before held my shiny black Stratocaster. And now its arms are clutching nothing. Now there is nothing.

***

I must’ve been drifting to sleep because I’m startled awake by footsteps on the attic stairs, and then Pam pokes her head between the banisters. “Are you sleeping?”

“No. You can come on up.”

As she enters the attic, Pam flips her dark hair off her shoulder, something Nikki does when she’s nervous. I sit up as Pam plops down beside me on the mattress. Smooth-skinned and full-lipped, Pam is totally sexy. For a sister-in-law, I mean. Damn, I already miss kissing Nikki.

“Listen, Pete,” she says, “Dwayne told me. About Nikki. I know you’re too proud to ask, but do you want to talk? I’m worried about you.”

“I’m fine.”

She places her hand on top of mine. “You and Nikki were together for a long time, Pete. You’re not fine. If you keep it all inside, it’s going to keep building. Talk to me. What happened?”

“She cheated on me with a chin-scratcher.”

“Was it that poetry teacher she had?”

“How did you know?”

“She was over here one night and telling me about him. It sounded suspicious.”

“I’m going to fucking puke.”

“I’m sorry, Pete,” Pam says and puts her arms around me. And then she pulls back and looks me in the eyes. And then, I swear, my sister-in-law wets her lips, and something comes over me, some surge of insanity, and carries me out of my mind. Like I did last night at the bar, I pretend she’s Nikki, and I lean in and plant my lips on hers, tasting the coffee on her breath.

Pam shoves me on my back and leaps up from the mattress. “What the hell are you doing?”

My hands fly up, palms open. “I didn’t mean it, Pam. I’m sorry.”

“What the hell are you doing, you asshole? Jesus Christ, Pete. That was not cool. Seriously, seriously not cool.”

“Pam, I’m sorry. I didn’t mean it. I want to talk about Nikki.”

But it’s too late. She’s halfway down the attic stairs by the time I get to my feet. With the lumps on my head throbbing like a metronome, I fling myself, face first, on the mattress and lie as still as a dead man and wait for Dwayne to come barreling into the attic.

Twenty minutes later, I hear their car leave the driveway.

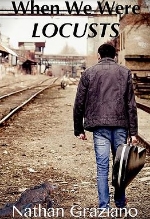

When We Were Locusts is now available on Amazon.